Retirement accounts lifts over one million seniors out of poverty

But the official poverty rate doesn't count IRA and 401(k) withdrawals as "income"

Part 2 of a series explaining how, evidence to the contrary, most Americans, most journalists and most policymakers believe the U.S. retirement system is failing. Drawn from The Real Retirement Crisis.

The New York Times, in 2023:

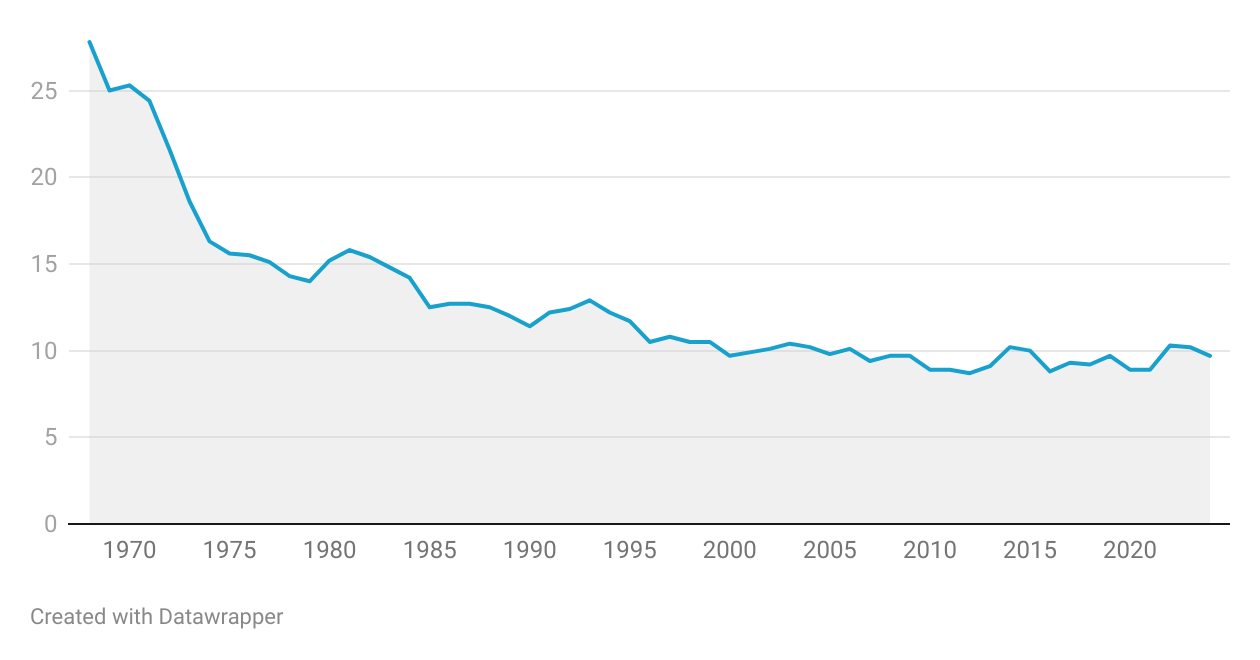

The proportion of older Americans living below the official poverty level fell drastically through the 1960s and 1970s, largely because of expansions and increases in Social Security. But there has since been a plateau.

“It’s not fully appreciated how persistent senior poverty has been,” Dr. Johnson said. “The decline really slowed in the 1990s and hasn’t improved significantly since.”

And seemingly they’re right. Just look.

According to official statistics, the 9.7% poverty rate for Americans aged 65 and over in 2024 was the same as in the year 2000, showing no progress in fighting elderly poverty in over two decades.

But what if I told you these statistics were just wrong?

And for a simple reason: the federal government isn’t counting seniors’ entire incomes. An important component is largely left out.

No, this isn’t something arcane like whether rent subsidies or health insurance should be counted as income in calculating poverty. (Some say yes, others say no.)

It’s whether what’s likely to be most retirees main source of income on top of Social Security, the thing that puts money in their bank account and food on their table, is counted as “income.”

I’m talking about withdrawals from retirement accounts, such as IRAs and 401(k)s.

The bizarre reality is that official government poverty statistics don’t count retirement account withdrawals as “income.” That doesn’t matter for kids or working-age adults. But it’s increasingly important for seniors, so much so that the official poverty rate for Americans aged 65, which largely ignores income from retirement accounts, is nearly double the true rate when retirement account withdrawals are included.

Read on.

The most common source of data on retirees’ incomes is the federal government’s Current Population Survey. It should go without saying that the government’s main data source on retiree incomes should, you know, count their incomes. Income, according to the OECD, “represents the money available to a household for spending on goods or services.”

However, the CPS measures what is called “money income,” which the Census Bureau defines as “income received on a regular basis.”

So a monthly Social Security check or pension benefit, or a biweekly paycheck from a job in retirement? They’re income.

But what about when a retiree draws down their IRA, 401(k) or other savings as-needed? Not income, as far as the Census Bureau surveys are concerned.

The problem with the Census Bureau’s definition of income shouldn’t be hard to grasp, especially as retirement accounts take the place of traditional pensions. One type of retirement plan, which is counted as income, is being replaced by another plan, which isn’t counted as income. Obviously this can skew our perceptions of how well 401(k)s have take the place of traditional pensions. Official statistics on incomes and poverty are literally useless in analyzing this change to the U.S. retirement system because they all-but-ignore the income seniors receive from IRAs and 401(k)s, the very savings vehicles that led this change.

Fortunately (for data nerds, if not for taxpayers), the Internal Revenue Service doesn’t give a crap where you got your income from. They just want their slice of it. Which means we have some alternate data to illustrate how big a problem the CPS’s mismeasurement of retirement income is.

For instance, in 2023, the CPS reports that seniors received $583 billion in income from retirement accounts, traditional pensions and annuities. By contrast, the IRS reports that seniors receive $1.0 trillion in retirement account, pension and annuity income, a 72 percent increase. Presumably, most of that gap is from retirement account income not being capture in the CPS.

This same error applies to income from ordinary non-retirement investment accounts. As I point out in The Real Retirement Crisis, the Social Security Administration was aware of this reporting problem as early as 1968: a survey the SSA conducted at the time captured less than half of the investment income that seniors reported to the IRS on their tax returns. Over time, as pensions were replaced by retirement accounts, the problem only becomes more widespread.

In 2014, pensions expert Sylvester J. Schieber and I pointed these problems out in the Wall Street Journal. But given the existing data, there wasn’t much more we could do with it.

Moreover, even many who acknowledged this accounting error thought fixing it wouldn’t matter much. Most retirement accounts belong to the rich, they thought, so accurately accounting for IRA and 401(k) withdrawals wouldn’t have much effect on the typical retiree’s income, much less the risk that low-income seniors fall into poverty.

However, the Census Bureau picked up the ball and has done great work since. Census’s advantage is their access to IRS and other administrative data at the taxpayer level, which they can match to the same taxpayers’ responses to the Current Population Survey. So Census researchers could analyze on a person-for-person basis how much the CPS understates total incomes.

Unfortunately, the most recent year for which Census has made detailed data available is 2018. But in that year, the median age 65+ household income of $55,760 shown using IRS data was 28% higher than the $34,520 median income reported in the CPS. It’s shocking that such a large error has existed for decades and continues to exist in official U.S. government data.

To put the figures another way, in the CPS the median over-65 household has an income that’s equal to 61% of the median under-age 65 household. Using more accurate IRS and other administrative data, the median retiree household’s income rose to 77% of under-65 incomes.

Moreover, the true poverty rate among age 65+ Americans in 2018 wasn’t the 9.75% reported in official statistics based upon the CPS. The true elderly poverty rate was just 5.75%. Put another way, official government statistics claim the poverty rate for Americans 65 and over is nearly twice the actual rate.

Retirees don’t simply have a dramatically lower risk of poverty than official figures claim. They have a dramatically lower poverty rate than other Americans. For comparison, using the same more accurate data, the Census Bureau finds the 2018 poverty rate for children was 15.6% and for working-age adults 9.5%.

Just to re-emphasize: this isn’t a philosophical debate. When a retiree files their taxes, their retirement account withdrawals are counted as income. If a retiree applies for a means-tested government program, such as Medicaid, their retirement account withdrawals are income. It’s only in measuring incomes for calculating the poverty rate that retirement account withdrawals are for some reason ignored.

But what about changes in poverty over time? Fortunately, two Census Bureau economists, Josh Mitchell and Adam Bee, published a study that matched CPS responses to administrative data over the period from 1990 to 2012, with a later update to 2015. We can add the Census Bureau’s 2018 figure to follow poverty in old age over a 28-year period. (Values for the missing years of 2013-14 and 2016-17 are interpolated.)

From 1990 to 2018 the elderly poverty rate fell from 9.7% to 5.7%, a 41% reduction in the risk of falling into poverty in old age.

And this dramatic reduction in old-age poverty occurred over the same period in which retirement accounts began to take over for traditional pensions, a process that many feared and predicted would lead to increased retiree poverty.

Now, the Census Bureau research didn’t account only for how the CPS survey understates income from retirement accounts. It also used administrative data to more accurately measure Social Security benefits, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits, earnings, and income from non-retirement investments. It’s not crazy to think that it’s catching these other income sources, rather than retirement accounts, that accounts for the dramatic change in elderly poverty.

But you’d be thinking wrong. Relative to administrative data, the CPS’s figures on earnings, Social Security benefits and SSI benefits have, on net, almost no effect on the number of seniors reported to be in poverty.

By far the largest reduction in 65+ poverty came from accurately measuring benefits from retirement plans, where more accurately measuring these benefits cut the 2012 elderly poverty rate by 1.2 percentage points. The second largest effect came from accurately measuring income from investments outside of retirement plans, such as interest and dividends. More accurately measuring investment income cut the over-65 poverty rate by 0.8 percentage points.

Unfortunately, the Census Bureau’s 2018 figures are the most recent accurate data we possess regarding the true incidence of elderly poverty.

But if retirement account withdrawals generated this same 1.8 percentage point reduction in the elderly poverty rate in 2024, over one million seniors would be lifted out of poverty.

It is truly shocking that, with so much on the line regarding Social Security reform and the future of household retirement savings, we do not actually know the incomes and poverty rates of seniors in the United States today. We know with near-certainty that the official statistics overestimate poverty and underestimate retiree incomes, but we don’t know what the true rates of poverty and level of incomes are.

Thanks for this very informative piece. I appreciate your efforts to educate readers as to the true state of retirement savings in this country. But good luck getting your voice heard above the noise. Today’s Barron’s cites the National Institute on Retirement Security as saying that “about 40% of older Americans rely on Social Security for their ENTIRE income in retirement”. Readers are sure to see that as a crisis.

To your point, the shortcomings (more recently, it's been noted that it also undercounts retirement plan participation - see https://www.ebri.org/content/retirement-plan-participation-and-the-current-population-survey-the-trends-from-the-retirement-account-questions) in the CPS have been well-known for some time (at least among academics) - to the point where you'd think any reference to it in retirement income assessments should come with a big *. But then, that doesn't feed the retirement crisis narrative...