What Pension Scandals Tell Us About Pensions

Employers will offer defined benefit pensions if they’re lightly regulated, putting employees and taxpayers at risk. If pensions are well-regulated, employers won’t.

The Wall Street Journal reports on dangerous levels of underfunding in church pension funds, which are not required to follow the federal funding rules that govern private sector “single-employer” pensions. Employees of church-run organizations such as hospitals have experienced significant benefit cuts when their pension plan – which previously told participants the plan was well-funded – ran out of money.

This isn’t the first pension funding scandal in recent years. In 2021, Congress was forced to pass a multi-billion dollar bailout of so-called multi-employer pension plans, which are jointly run by labor unions and employers across certain industries such as trucking and construction. Multi-employer pensions are subject to much less stringent funding rules than are plans run by a single employer, such as Boeing or General Motors.

And we’ve seen major pension funding problems in places such as Chicago, Detroit and Puerto Rico, with underfunded pensions pushing the latter two governments into bankruptcy and threatening Chicago with the same. State and local government pension plans are unregulated by the federal government.

But there is one class of pensions that is well-regulated: so-called single-employer pensions, which are subject to Department of Labor oversight. Single-employer pensions must fully fund their obligations, while assuming conservative rates of return on their investments; they must address funding shortfalls promptly; they must purchase benefit insurance through the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation; and they must vest employees in their benefits after no more than seven years of service.

Federal rules aim to ensure that single-employer pensions are well-funded, so benefits are guaranteed to retirees without posing a financial risk to taxpayers. These federal pension rules are much stricter than the regulations applied to church pensions, to multi-employer plans or to state and local government retirement systems.

But there’s one other important difference between single-employer pensions and these other more lightly-regulated pension systems: single-employer pensions have largely disappeared in the private sector while these less-regulated pension plans continue to operate.

And this hits at an important point: traditional pensions are attractive to employers, so long employers can deny benefits to many employees and don’t have to fully fund the benefits they do owe. But when employers can’t get away with those things, traditional pensions are no longer attractive.

The logic behind this is fairly straightforward, even if pension regulations are often complex.

The first thing to understand is that a pension doesn’t come for free. It’s generally assumed that if employers’ costs for one benefit go up, they compensate by reducing wages or other benefits. For instance, the Congressional Budget Office and the Social Security Administration assume that an increase in employer’s Social Security payroll taxes will be passed on dollar-for-dollar to employees via lower wages. So employees actually pay for their pensions, one way or another.

The second thing to understand is that running a pension plan under federal funding rules is more expensive than the way less-regulated pensions do it. In 2016 I calculated that if state and local government pensions were required to run under federal funding rules, their annual costs would increase by a factor of five.

This is real money we’re talking about. And those costs will be passed on to employees.

How do we know if those costs would be worth it to workers?

One way is by looking at how people invest for retirement when they’re doing it themselves. Most Americans don’t have traditional pensions, which offer a guaranteed benefit but at a high cost. Instead, most workers today have a 401(k) or IRA retirement account, where they must decide on the mix of risk and return that they prefer.

And when people are investing on their own, they don’t seek to replicate the guaranteed benefits that defined benefit pensions provide. Instead, most people invest about 70% of their account balances in stocks.

A stock-heavy 401(k) doesn’t provide anything like a guaranteed benefit in retirement. Far from it.

But what it does provide is a higher expected rate of return, which translates to lower contributions from every paycheck.

What does this tell us about defined benefit pensions? That the guaranteed benefits a traditional pension plan provides aren’t worth the high cost to employees, because – when given the opportunity to do something similar with their own investments – employees opt for a lower-cost, higher-risk formula.

All of this makes the nostalgia for traditional pensions you sometimes hear seem somewhat strange. After all, there isn’t anything preventing companies from offering DB pensions today. ERISA didn’t make traditional pensions illegal. It simply said that if an employer is going to promise pension benefits, it actually has to fund them. It’s hard to argue with that.

We can see the same dynamic in the history of private sector pensions. Prior to the passage of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, single-employer pensions were lightly-regulated.

Strict vesting rules played a big role in keeping pensions cheap. Currently, ERISA dictates that an employee must become eligible for pension benefits – or “vested” – after five to seven years of employment. But pre-ERISA, employers could require employees to work much longer before they qualified for benefits. These vesting schedules helped firms manage their workforces by giving employees strong incentives not to change jobs.

But they also had the effect of denying benefits to most of the employees who technically participated in a pension plan. For instance, in 1971 the Senate Labor Committee analyzed 87 private pension plans, who since 1950 had 9.8 million combined participants. Of the 6.7 million plan participants who had separated from their employers, 88% did not receive even a dollar of benefits.

And even among those who managed to collect, benefits were modest. The Labor Committee noted that “When the median for normal retirement of $99 a month [$832 in $2025] is added to the median Social Security retirement benefit of $129 a month, the total, $228 a month, is less than the $241 minimum monthly income required to sustain a retired urban couple, as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in January, 1970.”

This isn't exactly the Golden Age of retirement security.

But it is cheap, and that helped make defined benefit pensions more attractive to employers. Once ERISA tightened up vesting requirement, which made traditional pensions a better retirement savings vehicle for employees, employer costs increased, the ability of employers to manage their workforces was limited, and the overall attractiveness of DB plans to businesses declined.

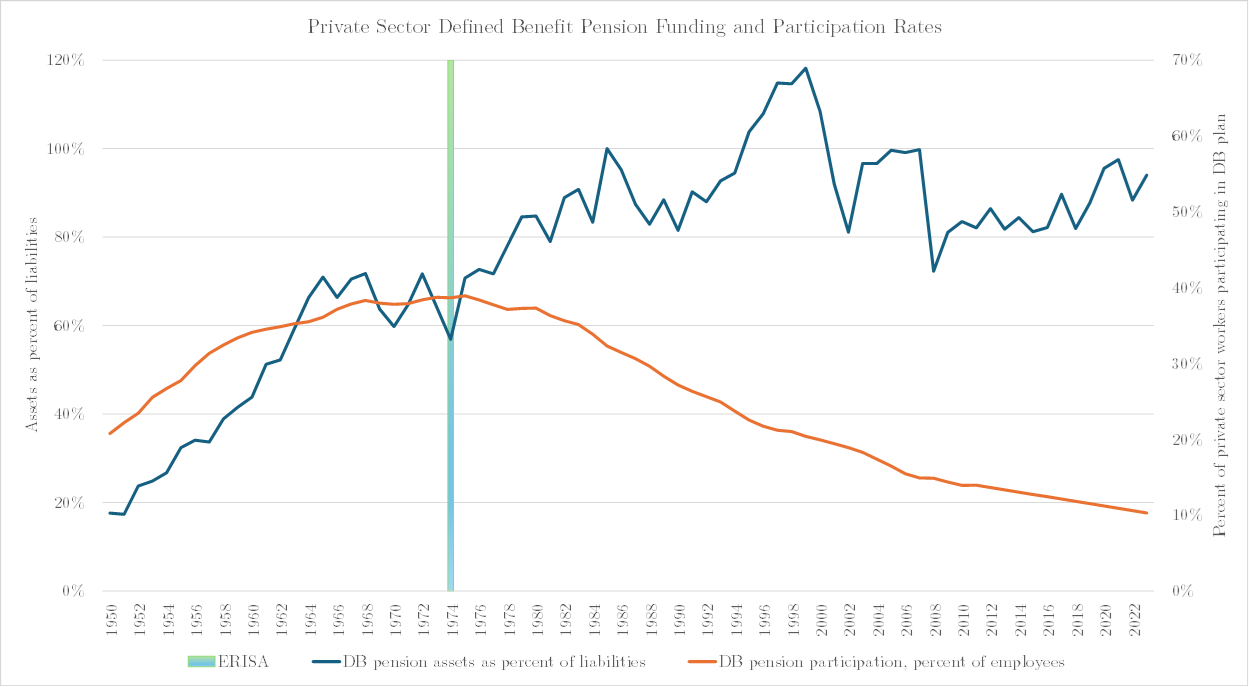

But there was a second factor. Prior to ERISA, there were no federal funding rules for pensions. Employers could fund them or not, depending upon their own preferences. In 1950, private sector DB plans were on average only 18% funded, according to Federal Reserve data. Moreover, because pre-ERISA funding standards were low, if the employer went bankrupt retirees could lose much or all of their benefits. That actually happened.

Funding increased over time, even prior to ERISA, such that by the mid-1960s private pensions were about 67% funded. (For context, that’s better than state and local government pensions are funded today, when the Fed compares plans using the same methods and assumptions.)

But ERISA clearly had a positive effect on private sector pension funding: by the mid-1980s, the typical private sector pension was about 90% funded, even when underfunded multi-employer pensions are included in the private sector total. While funding has fluctuated based upon changes in interest rates, in the most recent data for 2023 the average private plan was 94% funded. That’s a good thing, since it increases benefit security and reduces risk to the taxpayer.

But we can see that something else happened as well: almost as soon as ERISA passed, establishing vesting and funding policies that benefited pension participants, coverage by private DB pensions began to decline. In 1975 DB pension coverage peaked at about 39% of the workforce. By the mid-1980s coverage had fallen to about 32%, with continued declines until today only around 10% of private sector employees had a DB pension. And even for this select group, their plan is typically a scaled-down DB plan coupled with a 401(k) retirement account, or a cash balance plan, which is a traditional pension that’s built to look more like a retirement account. The traditional pension as we typically understand it is nearly extinct in the private sector.

In other words, there’s good reason to believe that solid regulation of private sector pensions – regulation that ensured the employees become entitled to benefits they expect and that employers fully fund those benefits – helped push DB pensions to the point of extinction.

This again points to the conclusion that, in the private sector, defined benefit pensions weren’t worth the cost. This doesn’t imply that DB pensions have no value. For employees who stick with the same employer over their entire career a DB plan can be great. What this means, though, is that employers could use the same money to provide wages or other benefits that employees found to be more valuable.

And so efforts to revive traditional pensions in the private sector run into a true dilemma: if pensions are poorly-regulated employers will offer them, but when pensions are well-regulated employers won’t.

Great article Andrew!

Nice article - thanks.

For what it's worth, a couple of thoughts.

One distinction between multiemployer/church/state-and-locals vs. single-employer private sector is that the former generally bases liabilities and resulting funding on expected-return discounting and the latter doesn't. That means liabilities are understated and contributions are lower, but I'd distinguish that from "costs" -- costs are what they are even when the actuary understates them.

Stricter vesting requirements add cost, and PBGC premiums are a real cost, as you note, that apply only to the latter. I haven't looked, but I'd be surprised if vesting differences are significant between the former and the latter these days.

Maybe a minor point, but my sense (from experience) is that, at least in the last few decades, GAAP accounting requirements and PBGC premiums probably have more to do with improved funding in private-sector single employer plans than ERISA funding requirements. There is effectively a tax (PBGC variable rate premium) of 5.2% of underfunding per year. That's a big incentive to fully fund.

And especially for publicly traded companies, accounting is a big deal. Retiree medical plans started disappearing almost immediately when corporations were required to include them on their books starting in 1993, and there are no ERISA funding rules or PBGC coverage for them. They disappeared faster than the pensions (probably because they were unfunded - no run-off)

Thanks again -- good stuff.